|

| 农业和农学 |

|---|

| 历史 |

| 农业 |

| 其他类型 |

| 有关 |

| 分类 |

刀耕火种,或称刀耕火耨、火耕,是一种以砍伐及焚烧林地上的植物来获得耕地的古老农业技术。民首先会砍伐一个地区的树木及木本植物,待树木干燥后再作焚烧,此举所产生的富含营养的草木灰能使土壤肥沃,土壤的生产力亦暂时性得以提升。在经过数年的耕作后,耕地会因养分大量流失而变得贫瘠,民便会弃置现有耕地并另辟新的耕地[1][2]。在印度,这种农业技术被称为“jhum”[3]或“jhoom”[4]。而在玛雅文明中,有一种类似的技术被称为“米尔帕(Milpa)”[5]。

此种农业技术对于人口增长迅速的现代世界来说不具备可扩展性及可持续性[6][7]。尽管如此,经粗略估计全世界仍然有7%的人口(约2亿至5亿人)使用此技术开辟新的耕地[8][9]。

历史

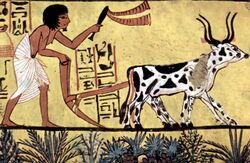

世界大部分地区都有着民使用刀耕火种开辟耕地的历史。在新石器革命时,人类开始由狩猎采集社会转型至耕社会,但随着人口增加,食物的需求亦渐渐增加,因此耕地变得重要。为了获得更多的耕地,人们开始利用刀耕火种这种技术来清除更多的土地,以供种植及放牧。因此,自新石器时代以来,刀耕火种这种技术已被人类广泛用于将林地转变为田和牧场[10][11]。由于当时的人口对土地的压力较低,而且人们的生计以自给农业为主,因此这种技术在那段时期是很有效的[12]。在历史上,居于欧洲、西非及南美洲等地的民均有使用刀耕火种的纪录[13][14]。另外在唐宋时期,部分农业民族例如畲族、苗族、瑶族、壮族等都主要以刀耕火种为主要特征[15]。

在19世纪和20世纪初,刀耕火种对一些人口较为稀疏的地区来说是一种可持续的技术,因为耕地有足够时间恢复营养。但随着世界人口爆增,轮耕的周期不断加快,民不得不将森林开辟为新的耕地,以致森林砍伐的问题日益恶化[1][7]。

应用

刀耕火种是一种在自给农业中经常使用的技术,除了开辟耕地外,民还会使用此技术用以开辟畜牧场。在旱季时,民会利用斧头及镰刀等工具砍伐林地上的树木及木本植物,当植物干枯一段时间,民便会在中午时份焚烧干枯的植物,而植物经焚烧后所产生的富含营养的草木灰则能使土壤变得肥沃[13][16][17][18]。

刀耕火种的稳定性大多取决于整个生态系统的总营养成分,而不是刀耕火种后土壤的净增益[19]。在土地开发的第一个周期中,刀耕火种将大量储存在地上生物量中的营养物质释放到土壤中[19]。因此,土壤中营养物质的增加是以植物生物量为代价[19]。尽管在刀耕火种后土壤的养分供应会短期增加,但另一方面,在焚烧林木期间大部分的矿物营养素可能会因为侵蚀作用或淋溶作用而流失,例如钾、镁、钙、硝酸盐及硫酸盐等[19][20]。另一方面土壤内的营养物质会因被作物吸收而减少,故整个生态系统中的总营养数量会逐渐减少[19][20]。当土地变得贫瘠,民便会利用同样技术清除林地并开辟新的耕地[16][17]。由于民经常从一个耕地转移到另一个耕地,因此刀耕火种可被视为轮耕的其中一种方式[21]。

在巴西,尽管清除森林是非法的,大量民仍然使用刀耕火种在亚马逊森林内开辟耕地,并种植经济作物如大豆及玉米等[22][23][24]。而在印度尼西亚,大部分的小使用刀耕火种来清除热带雨林,以便开发棕榈油种植园[25][26]。另外,部分农业企业更会向一些居于贫困村落的民支付金钱,要求他们清理他们的耕地以供种植棕榈树及生产纸浆,而民在收取金钱后便会使用刀耕火种来清理耕地[25][26]。

影响

在印尼苏门答腊和加里曼丹等地,由于大部分民习惯使用刀耕火种技术清理土地,以种植棕榈树及生产纸浆,因此森林大火及其衍生的霾害问题每年都会发生[27]。环保组织“绿色和平”指出印尼境内的雨林在过去数十年已经有超过四份之一被毁,更将矛头指向棕榈油企业及一些棕榈油消费品牌[28][29][30]。在2015年11月,“绿色和平”发现婆罗洲某一地区出现了灾情严重的火灾,更在数个月后变成了油棕种植园[29]。他们指此举不但摧毁宝贵的热带雨林,更会赶绝栖息其中的雨林动物,如红毛猩猩、长鼻猴及马来熊[29][30]。另外在2015年6月,由于非法的刀耕火种活动而导致印尼出现山火,其后更引起严重雾霾,并波及新加坡、马来西亚等国[27]。有研究指出在2015年该地区排放了8.84亿吨二氧化碳,其中97%来自印尼的山火,更表示二氧化碳排放量相较1997年的火灾更严重[31]。另一方面,有研究推算印尼、新加坡及马来西亚三国共有10.03万人因为2015年印尼森林大火而过早死亡[32][33]。

在巴西,有报道指出截至2017年9月发生于亚马逊地区的帕拉州的火灾相较2016年增加了229%[34]。研究人员指出大多数的山火都是人为造成的,原因是人们清除森林并将林地转化为耕地,而采矿公司、伐木企业和农业综合企业则加剧了森林退化问题[34]。尽管森林法规禁止任何人在大西洋沿岸森林进行刀耕火种,但破坏仍然存在[35]。有研究指出植物在被焚烧后所产生的残留物会因淋溶作用而流入河流并最终进入海洋,而这种被称为“黑碳(Black carbon)”的物质在进入海洋生态系统后更可能会伤害海洋生物[36]。

相关条目

参考资料

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Petra Tschakert; Oliver T.Coomes; Catherine Potvin. Indigenous livelihoods, slash-and-burn agriculture, and carbon stocks in Eastern Panama. Ecological Economics. 2007, 60 (4): 807–820.

- ↑ Rainforest Saver. What is slash and burn farming?. 2019-06-28 [2019-07-08] (英语).

- ↑ Sanjoy Choudhury. Jhum. Geography and You. 2010, 10 (59).

- ↑ Disha Experts. 1500+ MCQs with Explanatory Notes For GEOGRAPHY, ECOLOGY & ENVIRONMENT. Disha Publications. 2018 (英语).

- ↑ Roland Ebel. Effects of Slash-and-Burn-Farming and a Fire-Free Management on a Cambisol in a Traditional Maya Farming System. Redalyc. 2017-07-04 [2019-07-12] (英语).

- ↑ Nyle C.Brady. Alternatives to slash-and-burn: a global imperative. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment. 1996, 58 (1): 3–11.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Dale Bandy. Alternatives to slash-and-burn. A global strategy (PDF). International Center for Research in Agroforestry. 1994 [2019-07-10] (英语).

- ↑ Lynn Jenner. First Comes Fire Then Comes Crops in India. NASA. 2016-03-23 [2019-07-09] (英语).

- ↑ Ishan Y Pandya, Harshad D. Salvi. Significance of Tropical Woods of Southern Gujarat. Raleigh, NC: Lulu Publication. 2017: 206. ISBN 978-1-387-21570-6 (英语).

- ↑ Jaime Awe. Maya Cities and Sacred Caves: A Guide to the Maya Sites of Belize. Benque Viejo del Carmen, Belize: Cubola Productions. 2006 (英语).

- ↑ Henning Hamilton. Slash-and-Burn in the Historyof the Swedish Forests (PDF). Rural Development Forestry Network. 1997 [2019-07-10] (英语).

- ↑ Raju Chhetri; Pramod Prasad Dahal; Kalpana Pokhrel; Bishnu Maharjan; Saurav Suman. “Expedition From Slash And Burn To Agroforestry Plantation, A Livelihood Upliftment Subsequences Of “Bankariya Ethnics”:A Case Study Of „Manahari Rural Municipality‟ Within Central Nepal.. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention. 2018, 7 (7): 1–9.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Bart Wickel. Water and Nutrient Dynamics of a Humid Tropical Agricultural Watershed in Eastern Amazonia. Göttingen, Germany: Cuvillier Verlag. 2004 (英语).

- ↑ William Nganje, Eric C. Schuck, Debazou Yantio, Emmanuel Aquach. Farmer Education and Adoption of Slash and Burn Agriculture (PDF). North Dakota State University, Department of Agribusiness and Applied Economics. 2001 [2019-07-13] (英语).

- ↑ 曾雄生. 唐宋时期的畬田与畬田民族的历史走向. 古今农业. 2005, (4): 30–41.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Mark Cochrane. Tropical Fire Ecology: Climate Change, Land Use and Ecosystem Dynamics. New York, USA: Springer Science & Business Media. 2010. ISBN 978-3-540-77380-1 (英语).

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Marcel Mazoyer, Laurence Roudart. A History of World Agriculture: From the Neolithic Age to the Current Crisis. London, UK: Earthscan. 2006. ISBN 978-1-84407-399-3 (英语).

- ↑ Paul Clarence Challen. Environmental Disaster Alert!. Crabtree Publishing Company. 2005. ISBN 978-0-77871-581-8 (英语).

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 Anthony S.R. Juo; Andrew Manu. Chemical dynamics in slash-and-burn agriculture. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment. 1996, 58 (1): 49–60.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Christian P. Giardina; Robert L. Sanford; Ingrid C. Døckersmith; Victor J. Jaramillo. The effects of slash burning on ecosystem nutrients during the land preparation phase of shifting cultivation. Plant and Soil. 2000, 220 (1-2): 247–260.

- ↑ P. S. Ramakrishnan; Suprava Patnaik. Jhum: Slash and Burn Cultivation. India International Centre Quarterly. 1992, 19 (1/2): 215–220.

- ↑ Jonathan Watts. Brazil's Amazon rangers battle farmers' burning business logic. The Guardian. 2012-11-14 [2019-07-13] (英语).

- ↑ Sue Branford. A fight for Brazil’s Amazon forest. The Financial Times. 2017-09-20 [2019-07-13] (英语).

- ↑ Shasta Darlington. Brazil tries to balance farming and forests. CNN. 2012-03-19 [2019-07-13] (英语).

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Arlina Arshad. Indonesian firms pay farmers to be slash-and-burn 'fall guys'. The Straits Times. 2016-09-11 [2019-07-14] (英语).

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Kate Schecter. 'Slash and burn' in Indonesia: Getting to the root of the problem. Devex. 2015-11-30 [2019-07-14] (英语).

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 端传媒. 印尼森林大火后患无窮,研究指霾害致10万人早死. 2016-09-20 [2019-07-14] (中文).

- ↑ 绿色和平. 誰仍在火燒印尼雨林?. 2016-03-04 [2019-07-14] (中文).

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 绿色和平. 不可挽回的破坏 — 印尼雨林的无声吶喊. 2017-01-09 [2019-07-14] (中文).

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Hannah Gould. Palm oil giant's impact in Indonesia worse than reported, says Greenpeace. The Guardian. 2016-06-09 [2019-07-14] (英语).

- ↑ Thomson Reuters Foundation. Indonesia forest fires in 2015 released most carbon since 1997: Scientists. The Straits Times. 2016-06-29 [2019-07-14] (英语).

- ↑ Agence France-Presse. Haze from Indonesian fires may have killed more than 100,000 people – study. The Guardian. 2016-09-19 [2019-07-14] (英语).

- ↑ Shannon N Koplitz1; Loretta J Mickley; Miriam E Marlier; Jonathan J Buonocore; Patrick S Kim1; Tianjia Liu; Melissa P Sulprizio; Ruth S DeFries; Daniel J Jacob1; Joel Schwartz; Montira Pongsiri; Samuel S Myers. Public health impacts of the severe haze in Equatorial Asia in September–October 2015: demonstration of a new framework for informing fire management strategies to reduce downwind smoke exposure. Environmental Research Letters. 2016, 11 (9).

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Zoe Sullivan. Record Amazon fires, intensified by forest degradation, burn indigenous lands. Mongabay. 2018-01-18 [2019-07-14] (英语).

- ↑ Rachel Nuwer. Years After Slash and Burn, Brazil Haunted by 'Black Carbon'. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 2012-08-12 [2019-07-15] (英语).

- ↑ Thorsten Dittmar; Carlos Eduardo de Rezende; Marcus Manecki; Marcus Manecki; Jutta Niggemann; Alvaro Ramon Coelho Ovalle; Aron Stubbins; Marcelo Correa Bernardes. Continuous flux of dissolved black carbon from a vanished tropical forest biome. Nature Geoscience. 2012, 5: 618–622.